2014 Edition

Here is the scoop on how to vote and how the votes are counted.

San Leandro instituted ranked choice voting (RCV) in 2010. This will be our third election using it. I am a fan of RCV for a couple of reasons. First, it saves the city money to only have to conduct one election for Mayor/City Council – rather than an election and then a runoff. Second, it gives people more of a choice and allows voters to cast “protest” votes without fearing that this will help the candidate they like the least. Third, it costs less for a candidate to run one campaign rather than two (a regular one and a runoff). The cheaper the campaign, the less the candidate is indebted to his contributors

RCV has its detractors. Candidates that have a strong but discreet base (e.g. ethnic or other affinity groups) may prefer a plurality system, as they may be able to win without having to appeal to the majority of voters. Candidates that have a lot of money may prefer runoff elections, as the primary election may exhaust their opponent’s funds, making it easier to defeat them in the general. Special interest groups dislike RCV both because it makes it more difficult to predict who will win a race and therefore whom they should back, and because it dilutes the power of their endorsement and financial contributions.

How to Vote

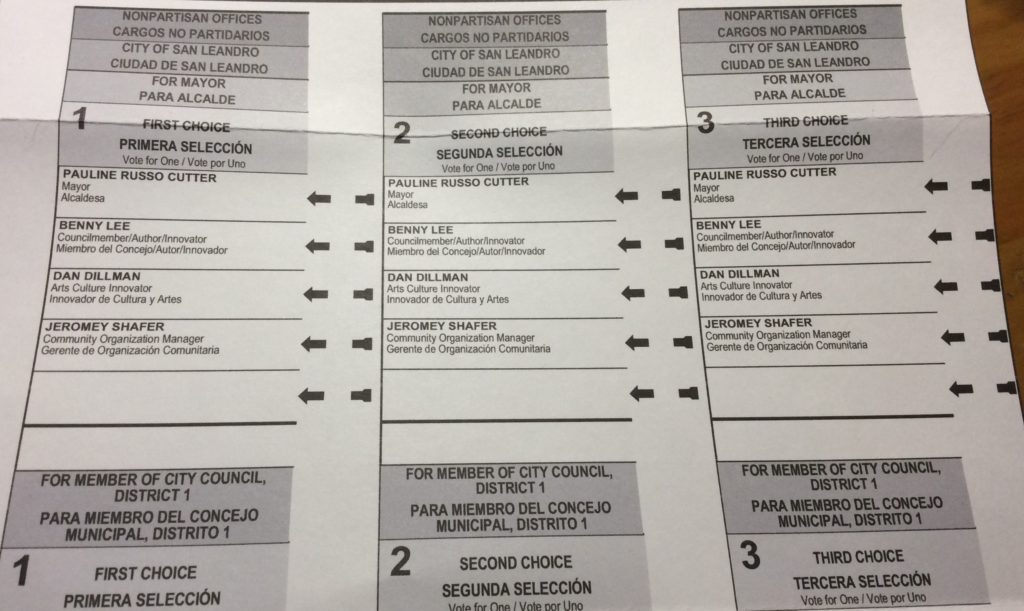

Voting in a ranked choice election is relatively easy. The ballot shows three columns marked “first choice”, “second choice” and “third choice”. Below them are the names of the candidates. You vote by completing the line next to the name of the candidate you prefer for that choice. Note that you must only mark one candidate under each choice, as otherwise your vote will not count. Importantly, ranking more than one candidate makes it more likely your vote will keep counting until the end of the count, and ranking a lesser choice never hurts your first choice.

To illustrate how RCV works, let’s say we have an election with four candidates: Smith, Chan, Jones and Garcia. Jones and Garcia are the two leading candidates, Chan is the middling candidate and Smith is the protest candidate – with a strong message but no chance to win. You support Smith’s message, but you want to make sure Jones does not get elected.

On your ballot, under “first choice” you fill the line next to Smith. For your second and third choices, you select Chan and Garcia. While the order is not important for your goal of making sure that Jones doesn’t get elected, if you mark Garcia as your second choice, chances are that your third choice, Chan, will not be counted, as Chan is likely to be eliminated before Garcia. If you prefer Chan to Garcia, you should put Chan as your second choice.

No matter how many candidates run, there are only 3 choices you can list. In a race with four candidates, this is not an issue, you just vote for the three candidates you prefer. In a race with 5 or more candidates, you may want to make sure that your third choice goes to a “safe” leading candidate, the least-bad option of the candidates likely to win.

How Votes are Counted

The process for counting votes is somewhat complicated and not in the least intuitive. Votes are counted in a rounds. An algorithm is used to determine how many votes each candidate has at the completion of the process. Here is how it works:

First Round: First Choices only

In the first round, the registrar will only count the number of valid first choice markings each candidate has received. Second or third choices will not be considered at all.

If a voter neglected to mark a first choice on her ballot, but marked a second (or third, if she didn’t mark a second either), then that second/third choices will be counted as a first choice. On the other hand, if a voter marked more than one candidate as his first choice (an overvote), then the ballot will be considered invalid and will be discarded, as the intention of the voter is not clear. This ballot will not count to the total of votes cast on that or subsequent rounds.

If any candidate gets 50% +1 of first-choices, that candidate is elected. If no candidate gets that many, then we go to the second round.

Let’s assume that 10,000 valid votes were cast in our imaginary election, with the first choices distributed in this manner:

Jones: 4,000

Garcia: 3500

Chan: 2000

Smith: 500

None of the candidates has 50% +1 of the first-choices – they would need 5001 – so Smith, having the least votes, is eliminated and the count goes into the second round.

Second Round: First Choices of top vote-getters + 2nd choices of lowest vote-getter

In the second round the registrar looks at the second-choices on the ballots that had marked the eliminated candidate as the first choice (Smith in our example). The second-choices are added to the count of the remaining candidates’ votes. Note that the registrar does not look at the second-choices for the ballots that have any of the remaining candidates marked as their first choice. That’s because every voter has one and only one vote, and your vote never counts for more than one candidate at a time.

Once again, if a voter has not marked a second choice, but has marked a third choice, then the third choice will be treated as the second choice. If the voter marked the same candidate as both his first and second choice, and that candidate is eliminated, then the registrar will look at the third choice and treat it as a second choice. If there are no 2nd or 3rd choices marked, or if more than one candidate is marked as a 2nd choice, that ballot will be considered exhausted/invalid and discarded and won’t count towards the total votes in that round.

In this and subsequent rounds, the registrar will count the number of ballots that remain valid, and calculate the percentage of the vote based on that number.

In our example, Smith got the least amount of first-choices so he’s out. Now we look at the 2nd-choices of the 500 people who selected Smith as their first-choice.

2nd choice on 500 ballots that marked Smith as first choice

– Jones: 150

– Garcia: 200

– Chan: 100

– No or Invalid votes: 50

Totals after 2nd round

Total votes: 9950

– Jones: 4000 + 150 = 4150 votes (42%)

– Garcia: 3500 + 200 = 3700 votes (37%)

– Chan: 2000 + 100 = 2100 votes (21%)

None of the candidates have gotten the required 50% + 1 of the vote, so the candidate with the least amount of votes is eliminated (Chan in this case) and we go to the third round.

Third Round: First Choices of top vote-getters + 2nd or 3rd choices of 2 lowest vote-getters

In this round, the registrar will count the second choices on the ballots that had marked the most recently eliminated candidate as first choice (Chan in our example), and the third choices on ballots that had marked the two eliminated candidates as their first and second choices (Smith and Chan in our example).

2nd-choices on 2000 ballots that marked Chan as first choice

– Jones: 650

– Garcia: 750

– Smith: 200

– No or invalid votes: 400

– Total votes so far: 9550

3rd choices on the 200 ballots that listed Chan as first choice and Smith as second choice

– Jones: 100

– Garcia: 50

– No or invalid: 50

– Total votes so far: 9500

3rd choices in the 100 ballots that listed Smith as a first choice and Chan as a second choice

– Jones: 20

– Garcia: 60

– No or invalid: 20

The total number of valid votes cast after the third round is: 9480

By adding the third-round votes to candidate’s totals we get:

– Jones: 4150 + 650 + 100 + 20 = 4920

– Garcia: 3700 + 750 + 50 + 60 = 4560

Jones got 51.9% of the vote, and thus he wins.

Gaming RCV

After much thought, analysis and reading, I am confident that it’s impossible for voters to “game” ranked choice voting. With four or less candidates in a race, you really should vote for candidates in your order of preference. There are a couple of caveats:

1) If you want to cast a protest vote, mark that candidate first, otherwise your vote may not be counted for her, and nobody would know about your protest.

2) If you are a candidate, you can become a second choice by teaming up with another candidate in your race. However, this can be a dangerous strategy. If your opponent/collaborator is a strong candidate, your help may make her win. If, on the other hand, she is a weak candidate, associating with her may hurt your standing with voters. A better strategy is to ask voters who have already committed to one of your opponents to mark you as their second choice.

3) If there are more than four candidates, the only change in strategy is to try make sure one of your three ranked candidates is likely to be one of the two strongest candidates in the final round. In such a scenario, your first choice is for the candidate you like the most, your second choice is for your 2nd favorite, and your third choice is for a candidate you can live with.

Note that while I speak about what the registrar will do, in reality the actually calculations are done by a computer using a preset algorithm.

Please let me know in the comments below if you have any questions.

—

This article was written with information provided by the Alameda County Registrar of Voters and Fair Vote. It has been substantially revised for the 2014 election. The omment below reference the original article written in 2012. My gratitude to Rob Richie from Fair Vote for his invaluable help with this article.